Researchers built 90 hair-snare stations designed to pull a small hair sample from black bears that cross the snares.

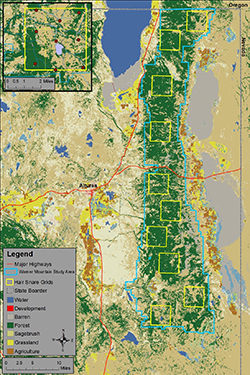

The Warner Mountains Black Bear Project study area (blue boundary) and layout of hair-snare grids (yellow squares) in northeastern California. The upper-left inset shows the southernmost hair snare grid and layout of hair-snare locations (red circles). Density estimates and information on habitat from within the 10 grids will help researchers estimate overall black bear abundance across the entire study area.

California’s black bear population is healthy and growing, with an estimated 35,000 animals, up from an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 in 1982. But how do wildlife biologists determine these figures – and why are they important?

Deep in the Warner Mountains in Lassen and Modoc counties CDFW is just completing the first year of a study of black bears. The lead scientist, Steffen Peterson, explained that anecdotal evidence in recent years – including increased bear sightings by both field scientists and everyday citizens, as well as an increased number of requests for depredation permits due to bear-human conflicts – seemed to indicate that the population of black bears in the Warner Mountains was booming and this area would be ideal for scientific research.

According to Peterson, the two primary objectives of the Warner Mountains Black Bear Project are to estimate black bear abundance in the study area and to determine how black bears use the landscape. This kind of information on black bear demography and space use is essential for wildlife managers to make scientifically sound bear management decisions for this region of California.

CDFW is using a genetic capture-recapture method to estimate the population size. Usually, this involves physically capturing an animal, marking it in some way and releasing it. But this particular study achieves the same goal with non-invasive techniques – specifically by using hair snares, which cause relatively little stress or harm to the animals. Hair snares have been used on many furbearing species to determine presence, to calculate a minimum absolute count of individuals present, or to estimate total population size by collecting a DNA sample from individuals without physically capturing the animal. Unique repetitive sequences, known as microsatellites, within the DNA sample serve as individual identifiers, making it possible to know when and where each unique animal was present.

In addition, because the DNA located within roots of mammalian hair can identify species, sex, and individuality, this genetic technique is ideal for researchers to estimate abundance as well as obtain information on demographics and genetic diversity.

Peterson, a CDFW scientific aid and a Humboldt State University graduate student, and other researchers built 90 hair-snare stations distributed across 10 sampling grids that that are designed to pull a small hair sample from bears that cross the snares.

The contraption consists of two parallel strands of barbed wire stretched around a cluster of three or more trees, one about eight inches off the ground and the other about 20 inches off the ground. This forms a barbed-wire “corral” in which researchers place a pile of logs drizzled with fish oil. The oil acts as an attractant to black bears, who have both a finely attuned sense of smell and a profound love of fish. At two thirds of the hair-snare stations, researchers placed a trail-camera to help verify the effectiveness of the snares at capturing hair samples when a bear is present. The trail photos also provide demographic (cub-adult ratio) information on bears within the study area.

“The use of hair-snares to collect genetic data for abundance and density estimates has become the gold standard for American black bear,” said Peterson. “The hope is for the bear to cross between the two strands of barbed wire, although some of our video footage from the trail cameras shows bears crossing – even jumping, in some cases – over the wire. Because bears are big, robust animals, for the most part they pay little mind to the barbs and typically cross them, leaving us a nice big clump of hair. Bears are the ideal critter for hair-snares in this way.”

Although Peterson stressed that it is much too soon in the study process to draw conclusions about the number of black bears living on the grid, initial results indicate that, at a bare minimum, black bears are certainly roaming throughout the study area.

During a 50-day hair collection period that took place this summer, black bears were detected in all of the grids created in the study area that encompasses roughly 600 square miles of high desert terrain; researchers collected 469 samples of hair in all at 57 of the 90 hair-snare locations.

“Long story short, we are pleased by the amount of detections observed during our data collection,” Peterson said. “Good detections will strengthen our ability to estimate density within each grid which will allow us to more reliably estimate abundance off the grid – i.e., the Warner Mountain study area as a whole.”

Peterson is now set to begin the DNA analysis phase on the samples collected. This will allow him to determine precisely how many individual bears left hair behind (bears often leave more than one sample at a snare location and some individuals are repeat visitors), as well as information on gender and habitat use, including the movement of bears across the study area.

Next summer, project staff will capture and collar 12 adult black bear with research collars, which will record hourly GPS locations of the bears as they move across the landscape, providing information on how they use the landscape, including seasonal habitat preferences and, during the winter hibernation period, where bears den.

“This information will greatly improve our knowledge of how bears use these high desert ecosystems, characteristic of the Great Basin, and guide future land management in this region,” Peterson said.

The project is expected to continue for another two to three years. ###

CDFW Photos. Top Photo: Emily Monfort, a CDFW scientific aid, carefully removes black bear hair from barbed wire at a hair-snare location. The DNA from this clump of hair will be examined in the laboratory to determine the sex and genetic identity of the black bear that crossed this wire. Photo credit Korrina Domingo (CDFW).